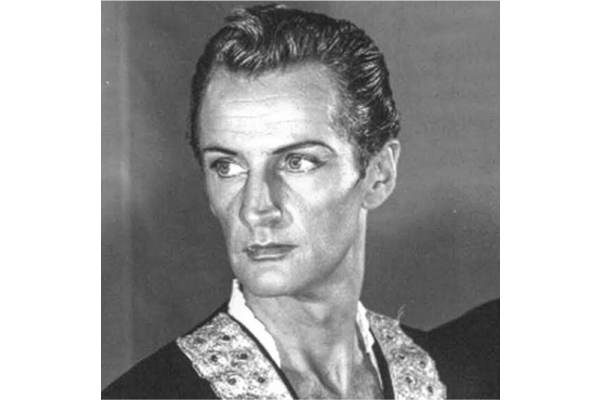

BALLET LEGEND HENRY DANTON TALKED TO DAME MONICA MASON

18th May 2021

Introducing the meeting, Susan Dalgetty-Ezra explained: “Eighteen months ago, Dame Monica asked me if I knew Henry Danton and, to my shame, I had to say ‘no, I don’t’. ‘Well’ she said, ‘I think he would be a tremendous guest for the LBC.’”

It was then planned to interview him in person when he was in London in March 2020 but Covid restrictions prevented this and a second attempt, by Zoom some months later, was defeated by a technical glitch.

“But tonight we have succeeded,” said Susan. “ And tonight is really appropriate as today would have been the 102nd birthday of Margot Fonteyn.”

Dame Monica began the interview by asking Henry to outline his early life and how he came to follow a career as a dancer. Born in 1919 in Bedford into an army family he was only three months old when his father died. His education was completed through what was known as a King’s Cadetship attending military-orientated boarding schools. At the outbreak of World War Two, he was a Second Lieutenant serving in the Royal Artillery. “I never wanted to be a soldier, it was completely against my feelings,” he explained. This soon led to a nervous breakdown and he was put on sick leave, being discharged from the army 18 months later.

“At some point you must have seen a ballet performance?” queried Dame Monica. Henry said that had happened when he had attended Covent Garden to watch the De Basil company performing during its London season. One of the ballets on the programme was Massine’s Jardin Publique that featured a statue that came to life. “That really impressed me,” he said. “That was my first introduction to ballet but I had no idea at that time of becoming a dancer.”

But surely, said Dame Monica, there had at least been music while he was at military school? No, he replied, except for one of the coaches who had a gramophone and played records for the students. And there was a brass band “but that only played for us to march around!”

Henry’s transition to dance came about because he was a keen ice skater and that included dancing on ice with a young female partner and it was the girl’s mother who encouraged him to take dancing lessons. “She was the one who took me to Judith Espinosa’s school. That’s how I started.” And he discovered he could easily do the ballet exercises because of his skating experience. “Espinosa said to her secretary: ‘Look at this boy, he’s completely natural.’”

Henry attended the Espinosa class in London once a week and, on other days, he went to a local school a bicycle ride away from his home where the first thing he learned was grand pliés. “And every day I did about a hundred pliés and then a hundred grand battements, that was how I learned, he said and added: “ I was doing the dancing without my family knowing as they would not have approved.”

He stayed with the Espinosa school for about 18 months during which time he was entered into and passed all the RAD exams plus the Adeline Genée. He was noticed by two American former dancers with the De Basil company who offered him his first job at the small, short lived company they had formed called Allied Ballet. “I went right into the company and had to learn Les Sylphides and two other ballets,” said Henry. “ I had to go out on stage and I had no idea about anything.” The job only lasted two weeks before the company folded.

As luck would have it, also taking classes at the Espinosa school was Mona Inglesby and she now offered Henry a job with her International Ballet. Not only that but she took him on as her dancing partner in Les Sylphides. “We had private lessons every day,” he recalled. “ And I also danced the second act of Swan Lake with her. It was just ridiculous. I had under two years’ training.”

Dame Monica wondered whether his ice skating experience had helped with partnering and lifting? “No,” he replied. “There was no lifting in the skating. The only dancing we did was ballroom dancing.”

Nevertheless, Henry decided he should progress to a larger company and approached Ninette de Valois at the Sadlers Wells Ballet. “She knew of me already as she had been a judge at the Adeline Genée (where he won a silver medal). She said she would take me if I could get out of the contract with International Ballet.” After some effort he was successful in this and left Mona Inglesby’s company after six months. He was also now receiving training from Vera Volkova.

Dame Monica wondered, if Robert Helpmann was at Sadlers Wells when Henry joined? Yes, he confirmed. “My first job was as a pall bearer to carry him on in Hamlet.”

Henry felt his move to Sadlers Wells had been a good one. There was, at that time, a shortage of boys dancing and, before long, he found himself in the Swan Lake pas de trois which he described as traumatic. “I hadn’t mastered double turns in the air. I was right back in the frying pan.”

However, during three years at Sadlers Wells (1944-46) he danced every ballet that the corps performed in. He described it as a very productive period; a turning point in his life. During a tour with ENSA to entertain the troops in Europe he went to Brussels and Paris and while in the latter he encountered the teacher, Victor Gsovsky who would come to play a significant role in his development. “In two weeks he taught me a great deal,” he said. When that Sadlers Wells season ended he decided the return to Paris to pick up on his training but de Valois wouldn’t let him go.

Dame Monica asked when he had first learned that Sir Frederick Ashton was going to make Symphonic Variations?

“He came to a performance, probably at The New Theatre, we were dancing Dante Sonata and I loved that,” said Henry. “It was passionate music and wonderful choreography. I just went to town on that and he saw it and invited me for a drink. I think he was sort of interested at that point. I suppose he saw some sort of possibility. I could jump well.” Henry would go on to dance in all of Ashton’s other creations at that time.

Dame Monica asked if Symphonic Variations had been rehearsed in the National Gallery? Yes, said Henry. “ They gave us the entrance hall. It was wonderful. There was a huge amount of space. The benches were still there. We hung onto them, but the floor was terribly hard. We all had problems with our ankles. I had my ankles permanently bandaged during that season.”

Did he remember the first night of Symphonic Variations at Covent Garden? “I certainly do,” he replied. “ There was a lot of interest. Fred had kept everyone out of rehearsals except Volkova and Sophie Fedorovitch, the designer. Fred designed each part on the particular facility which each dancer had. I could jump well so I got a lot of jumping.” “And,” he added: “the interesting thing was, when it finished, the curtain came down and there was absolute dead silence and we all thought ‘My God, it’s flopped!’ and when the curtain opened again the public just went mad.”

“It was,” said Dame Monica, “a landmark in Sir Fred’s career. Today, dancers adore dancing in that ballet but it is an absolute killer; you don’t leave the stage and it requires enormous stamina.” Henry agreed. “And it’s extremely difficult dancing. I look at it now and I think how was I ever able to do that? It was exhausting. When we were rehearsing it we, all six of us, were lying on the floor panting and Fred actually considered finishing the ballet!” Henry had danced that first performance with Margot Fonteyn, Pamela May, Moira Shearer, Michael Somes and Brian Shaw.

Dame Monica asked what happened when Henry left Sadlers Wells? “I left de Valois for a year off to study in France. I asked her if I could go and she refused, so I went anyway,” he said. “I left for France with £30 in my pocket. “Gsovsky was teaching for Roland Petit’s company, Ballet des Champs Elysée. They went on tour and I went with them.” He spent a year in France before coming back to England, asked de Valois to take him back, she refused, so he returned to France once more.

“I was very fortunate, Things always happen to me without my doing anything,” he said. He next found a job as a partner with the Paris Opera danseuse etoile Lycette Darsonval who was on leave from her company doing a personal appearance tour around France and Western Europe.

Following this it was back once more to England, an approach to de Valois who again refused to take him back so he took a job in London with the Metropolitan Ballet where Gsovsky was also teaching. After a further year the USA beckoned and, undaunted by the fact that it could take weeks or months to arrange a visa, Henry went to the US London embassy and discovered that the clerk he was speaking to was a ballet fan: “ So I got my visa in about five days – unheard off. So I went off to the US with £100.”

Staying with an American dancer in New York who had a spare room Henry went straight away to enrol for classes in Balanchine’s Madison Avenue school and, on days when he was free, checked into a second school run by a Danish woman called Madam Anderson. And during this time he met (Milorad) Mišković who had just arrived in New York with the Roland Petit company, Ballet de Paris. “Mišković told me he was sick with tuberculosis and had to return to France so I said ‘give my number to Roland and say I’m here.” The plan worked and Henry found himself with the Roland Petit company on a six-month tour of America and Canada.

Then, “out of the blue” he received a telegram from Australia from a couple he had worked with at the International Ballet who had set up the National Ballet of Australia. He was invited to join them as a guest artist for a four-act version of Swan Lake. So it was off to Australia where he toured for a year. “We did Swan Lake night after night,” he recalled. “After it finished, a newspaper said that my partner Lynne Golding and I created a Guinness world record for the maximum number of Swan Lakes.” Dame Monica added: “And she must have done thousands of fouettés.”

When Henry’s contract in Australia came to an end, he and Golding left for England but no sooner had they arrived than a telegram came to say that the couple who had set up the Australian ballet company had resigned and would he come back to be director? So, after just a month in England, he returned with Golding and began to rehearse Giselle but now the Australian government refused a grant to subsidise the company so the couple headed back to England en route to the United States.

Dame Monica wondered if all this globe trotting was done by ship but Henry said it was all by plane except for the final return trip from Australia. For this he and Golding had secured passage on an Italian cargo vessel heading for Marseilles. “We did our barre on the deck during the day and danced for the sailors in the evening; it was wonderful,” he said.

Once back in London Henry needed an operation on his ankle and was told to stop dancing for six months. Then came another “out of the blue” moment. A telegram from Caracas asking if he would come and teach, an offer he accepted because, although he was currently unable to dance, teaching was no problem. He set off for South America “where there was a wonderful dictator who was bringing Venezuela into modern times. I went for six months and stayed for two and a half years!”

He taught in a small school in a drawing room converted into a studio but before he left had created the National Ballet of Venezuela. Then eventually a revolution removed the dictator and everyone who had profited from his regime in any way was thrown out. Henry found himself with no money. A local tv station, where he had done a weekly ballet programme, failed to pay him so he went to the British Consulate to see if he could be repatriated to the US.

And luck was once more on his side. “The Consul was Freddie Ashton’s brother! He said, ‘ I can return you to England, but not to the US.’ So it was back to England.” At this stage history was repeating itself once more. On his return to London, he received a telegram from Caracas to say two students from the former ballet company there were re-starting the ballet school and would he come back, which, of course, he did.

This job continued until his former Australian partner, Lynne Golding, who by now was teaching at Carnegie Hall in New York, got in touch to say she had recommended him to the city’s Ballet Arts and they were offering him a teaching post. He went, and stayed in the job for more than eight years.

Dame Monica asked who had most influenced Henry’s teaching style? It was definitely Volkova, he said. He couldn’t quite remember how she taught but she had a wonderful gift for imagery. Also among his mentors were Gsovsky and other Russian teachers who had been in Venezuela. His main influences had definitely been Russian.

Dame Monica asked about the outcome of his ankle injury. He replied that during his period off from dancing he designed costumes, organised scenery and went in search of suitable music for productions. But he also stopped dancing at that point and devoted himself to teaching, which he carries on to this day in his home town in Mississippi. He had only attempted choreography once but decided he had no talent in that direction. “I love being a teacher, it’s fascinating, never ending,” he said. “You learn something new every day.”

Turning to modern day technique, he agreed that what dancers were able to achieve nowadays was “unimaginable years ago.” Dance had become so athletic, but he feared “the reason for dancing has gone completely. Nobody says anything with dancing any more. That’s the general tendency. I think that has been lost.” This was something he spoke to his students about. He also wrote a lot on the subject. “I protest, sometimes it gets listened to, sometimes not. I have a voice and I do say things. Dancers have to express something rather than a mechanical thing that has no meaning.”

Questions from the LBC Zoom audience were many and varied.

One questioner wanted to know how Olga Preobrajenska had taught at the Salle Wacker in Paris?

Henry commented: “she was very small and very old. She’d get up onto the piano, there was a window behind the piano. She’d feed the pigeons. She had a watering can, she would go around watering the floor so they wouldn’t slip. She would forget what she’d done, she would give the same steps twice. You just wanted to hug her. She was a beautiful person.”

Another wondered whether his family eventually came round to the idea of his being a dancer? “Yes,” he said, “ finally, it took a long time. Coming from an army background they thought I should be a major general in charge of the British Army. That was a disappointment to them.” But they came to see him dance at Sadlers Wells.

A questioner wanted to know if, when dancing at the International Ballet, he had memories of Sergeyev? Henry said that when he was there Sergeyev was setting Giselle for Mona Inglesby and while on tour he would rehearse with stacks of notation books but would sometimes get confused. When this occurred, his young French wife would step in to help. But while he was teaching Henry would go behind the backdrop and dance every role as he taught it. “I learned every single step, I was an absolute sponge,” he admitted.

Another question was whether dancers had sufficient to eat during the war and rationing? Henry said that was a real problem. Dancers had food stamps but, while on tour, had to give these to landladies running the lodgings where they stayed. “We didn’t all get our fair share. We were all undernourished. They called it the Sadlers Wells disease. We didn’t dance by muscles and bones, we danced by spirit.”

During the interview a video had been played showing Henry watching a British Film Institute clip taken from the dress rehearsal of Symphonic Variations. Henry had more information and an appeal to make. “On the second night, Ashton arranged for a movie camera to film the ballet but we never got to see it. That film exists,” he said, “I want to put out a plea to the person who is sitting on that film to release it because it’s history.”

Winding up, Susan thanked Henry and Dame Monica and said she hoped we could all meet for a face to face further interview when Henry returned to London next March to celebrate his 103rd birthday.

Dame Monica commented: “There’s nothing you wouldn’t do to talk to Henry Danton. He’s a living legend!”

Report written by Phillip Cooper and edited/approved by Henry Danton and Dame Monica Mason

© LBC

There were four additional questions that there was no time to answer during the Zoom conversation. These were sent to Henry afterwards and he has answered them as follows:

1. Re: Symphonic Variations

I would like to ask Henry how long the dancers spent learning and rehearsing this ballet, seeing that it is 21 minutes of abstract, complex movement. Also did Ashton choreograph extempore at rehearsal or did he come with notes already formulated? Thank you! Lesandre

Henry replied: Symphonic Variations started to be choreographed while the company was on tour (with a schedule that included three Saturday performances and a Wednesday matinee). So you can imagine with regular rehearsals and performances there was very little time and very little energy on the part of the dancers. When we came back to London – this was before the opening of Covent Garden – things were different. There was more time for rehearsals. They also had to be jammed in between rehearsals for the upcoming production of Sleeping Beauty at Covent Garden but it got done somehow.

About the way Ashton proceeded. He never came to a rehearsal with a piece of paper in his hand. Of course he must have done a great deal of thought in the evening before so he must have had some idea about what he wanted to cover during that day. But of course one has good days and bad days and he would have a day when no creativity at all and not much got done. So it wasn’t a regular day by day turning out sausages! It was done when we had time, when he felt like it.

You asked if he extemporised. Yes he did. I’m sure he’d done some preparation the night before but, when he actually rehearsed, he did it on the spur of the moment. Some days he would come in and change everything he’d done the day before because he had a better idea. So it was really a miracle that this ballet got produced at all given the conditions and the amount of time we had to rehearse. That probably makes it special the way it is.

2. Hello, Henry. Lovely conversation with Dame Monica Mason. My question concerns the passage of running in Symphonic Variations that you've spoken about. If I remember correctly, you've said something to the effect that the original cast had a specific reason in mind for why you all were running--that the movement alone wasn't Sir Frederick Ashton's masterpiece but rather that it was the movement plus the intention that made the ballet so vivid. Do you believe that the choreographer's intention, as conveyed to the original cast, is part of the text of any dance work? That it should be part of a staging? Or should each dancer be given the responsibility to search for that intention individually, as the movement might reveal it? Mindy Aloff, Brooklyn, New York

Henry: Ashton, when he was creating narrative ballets, was meticulous to the point of the limits of exaggeration, insisting on getting what he wanted so Symphonic Variations was a departure from that. Whether it happened by itself or was intended I don’t know. You also asked about other choreographers, I can’t answer for them but it is up to the choreographer either to leave the interpretation of what he has done to the dancers or to insist on his special interpretation. That depends on the choreographer and also on what he is doing. The choreographer has the right to do whatever he wants with any specific work.

3. Is there a book about Henry’s career? Catherine.

Henry: There is actually no book that I know about, about me. But there are two publications made by an ex very favourite student of mine who later become a teacher. And she put together a collection of photographs of me which she put together in a book which she called Metamorphosis of Henry Danton. This book she had put together by Shutterfly. It was like a private publication. I think one could access it with the permission of the author who was Katya Orohovsky. She subsequently made a second book, this time with my collaboration, the first one she did with photographs she got from off the Internet, whatever, without even telling me. The second time we did a somewhat larger edition, also photographs with explanatory captions and it was published, if you can call it published, printed by Shutterfly, a very limited number of copies, one copy of which I took to London to one of my birthday parties and had all my ballet friends sign it and it was then put into the archives of the Royal Ballet in Covent Garden. Whether you can access that or not is a doubtful question. It is there with all the signatures. I have made scanned copies of both of these books and I will find out with Katya’s help and permission if I can send them to you because I think the original has now expired and can no longer be reprinted. Otherwise the only place you can go is to Wikipedia. I neglected the title of the second book is Becoming Henry Danton.

4. This question is from me! You said you danced with Celia Franca. I'm curious to know if she asked you to come to Canada when she went off to set up The National Ballet of Canada? Susan Dalgetty-Ezra

Henry: When Celia moved to Canada we continued to correspond by email and telephone a great deal. She had been such a big influence on me and a mentor. She was a self-made person, pulled herself up from where she was originally and made herself into something. Absolutely fantastic and very intelligent. She was an enormous influence on me. I missed her a lot. Each time she was setting one of the ballets in which we both danced at Sadlers Wells she would sometimes call me if she could not remember a particular part or a particular number and I would help her out if I could also remember. Later, my sister who lived in Ottawa had her 80th birthday and I invited Celia and she actually came. I don’t remember what year it was but it was the first time I had seen her in many years and I was surprised to see that she had exactly the same hairdo but with white hair. I always remembered her with jet black hair and a flashing personality. I have photographs of that birthday party and of her and I will try and dig them up because I always like to substantiate anything which I say.

In conclusion, Henry added: “This has been such a wonderful experience with the London Ballet Circle. I have enjoyed it so much and it has given me so much pleasure and I’m so happy to know it was well received. “

© Copyright London Ballet Circle

It is with great sadness that we share the news of Henry Danton's passing on February 9th, 2022 just weeks before his 103rd birthday. We will always be grateful to him for his enthusiasm for the LBC, his "In Conversation" with Dame Monica Mason and his contribution to the 75th Anniversary Celebration.