Shale Wagman and António Casalinho ‘in conversation’ with Amanda Jennings

7th February 2022

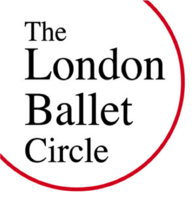

Shale Wagman and António Casalinho are rising stars of the ballet currently dancing with the Bayerisches Staatsballett in Munich. Shale is twenty-one and comes from Canada while eighteen-year-old António is Portugese, and their different backgrounds were explored ‘in conversation’ with dance writer Amanda Jennings. The evening focussed on the reasons why they became dancers, the various stages of their training, and their philosophies of dance as an artform. Both had been Prix de Lausanne winners.

The Chair of the London Ballet Circle, Susan Dalgety Ezra, welcomed the two dancers and thanked them for agreeing to the interviews. Amanda commenced the conversation by asking about the schools in which they had their first experiences of ballet. António explained that his first teacher was Annarella Roura Sanchez, a Cuban dancer who in 1996 founded a school in Portugal based on Cuban Ballet School methods. António had started to dance at eight years old, although at first the emphasis was simply on having fun. Annarella had connections in Cuba with some of the best teachers who over the years would each spend 3-6 months in Portugal at her school, and whose abilities in teaching raised the standards of the school.

The school was small and consequently training had been very personal, whether in class or rehearsal. It had involved much more than classical ballet, for instance contemporary and character dancing were also important. Georgian dancing was very good for developing male technique, for co-ordination and strength. António believed participation in competitions was useful because it introduced you to a range of dancers from other countries and backgrounds, and also furthered experience of actually appearing on stage.

Shale had been in love with dance from very young. He had started in competitive dance in North America at the age of six, involving jazz, tap, contemporary and modern dance but not a lot of ballet. He had starred in a number of full-length contemporary dance productions while still young. He found that he could learn choreography quickly. By thirteen he had decided that ballet was his future. Fortunately a competition prize had offered a scholarship and he chose to move to the Academy of Monte Carlo. He stayed 4 years and at seventeen entered and won the Prix de Lausanne. He enjoyed contact with all the other talented students. Dance was a very personal activity to Shale. He liked to feel a close connection with his directors and all those around him and found his teachers very nurturing. Amanda commented that both dancers had stressed the importance of individual attention during training. However, although both had been successful at the Prix de Lausanne and won other prizes, she wondered how they now viewed competitions? António agreed that he would compete again. Competitions had an important role in education. They were motivating; they could give purpose to training. They provided the opportunity to experience the great world of ballet, even if you didn’t win.

Shale had learned a great deal from the many regional and national competitions he had entered. They had provided experience in working co-operatively, and in working with some of the best directors. He had met so many other dancers with whom he remains in contact. He also explained that he was fascinated by watching others dance. When very young he had to be pulled from the wings by his mother because he just wanted to stay and watch all the others perform! He would watch anything and everything. Dance was all about energy and enthusiasm, and he put a lot of pressure on himself because he wanted to win. He occasionally felt that others did not fully understand his deep-seated need to dance.

At this point two video clips were shown. The first showed Shale dancing Basilio’s variation from Don Quixote at the Prix de Lausanne in 2018. Amanda commented on Shale’s virtuosity, that you could see he was an artist as soon as he walked from the wings. His whole body was involved in communication of the role. Although this attribute was not unique to Shale, it was less than common among dancers. The second video clip was also from the Prix de Lausanne and showed António dancing the Boy’s solo from Diana and Acteon. She commented on the great technique which he displayed, including two triple tours en l’air in succession. Amanda went on to ask both dancers how they now viewed their own work, and ballet itself as an artform.

Shale replied that it was difficult to put into words just how he felt as an artist on stage. It seemed to connect him with some higher order; it felt like ‘connecting with the universe’. He explained that he was a thrill seeker who loved emotions; he never wanted to play anything safe. He wanted everyone to share his story and his life. And to Shale spirituality and faith were extremely important. António was usually calm before a performance but as he steps on to the stage he immediately gets the feeling that he must accomplish everything perfectly. You see the audience, you see all those around you, and you feel capable of doing anything. You want to share all your energy with your fellow dancers, with everyone. Sometimes you achieve something and afterwards you really have no idea how you have done it.

Shale commented that he still likes to watch as a spectator and observe how the audience accept that energy from the stage. In a sense it doesn’t matter too much if a dancer makes one or two mistakes because for the audience it is all entertainment, which is the vital thing: “What about your current contracts?” inquired Amanda. “The Munich ballet has a great repertoire”.

António replied that he loved Munich. He felt that he had ‘not enough hands’ to catch all the opportunities being presented to him. It was his first year in a company; he was in a part of the world he didn’t know. Everything was different from the world to which he was accustomed. It was so exciting! As for the German language – well, he must have learned something in the 6 months he had been there… There was no problem within the company because so many languages were spoken, for instance, English, Portuguese and Spanish. Shale felt settled and was also very happy. He likes and gets on well with the choreographers and the company. He hadn’t felt that the early stages of his career had been great. It did not seem that the ENB (where he had danced for a year following his success at the Prix) had been the right company for him. He had been unemployed just prior to coming to Munich. COVID had intervened and put his career on hold, as it had with so many others. However, he feels that he can do anything now.

The dancers were then invited to respond to questions posed by London Ballet Circle members. António was invited to comment on the fact that, even though still very young, he had already danced the role of the princes in La Sylphides, Giselle, and Sleeping Beauty. In a sense much was due to the pandemic which forced tuition to go online. He had the fortune to be taught regularly by Maina Gielgud who had recognised his talent, and he learned much of the content via Zoom! He explained that Maina had been extremely good for him, developing his ability to act and tell stories.

Shale was asked whether he planned to undertake more choreography. In some competitions early in his career the choreographer involved might not finish a solo, telling Shale to improvise the ending. This gave him the impetus to choreograph; that and his great love for classical music. Often when listening to a piece of music he would formulate steps in his mind. However, what was important for now was to establish himself as a reliable professional dancer with the company.

He was then congratulated on his apparent ability to pick up roles at extremely short notice, responding that dancers can drop out at the last moment for all manner of reasons and one needed to be prepared. He was also asked about his guesting at the Mariinsky in St Petersburg. This had been a ‘dream come true’ for someone of just nineteen and for a while he had thought that he would stay with the company for the rest of his career. António was asked how he dealt with enormous challenges. He stressed that what the audience wants is emotion; it is as important as big jumps and other fireworks. The dynamics of the role – the placing of the head and arms, etc – all had to be right. Both dancers were asked how different company life was from school, responding that the work was more intensive, with several ballets in production at one time. There was also a realisation that the dancer has to pace him or herself if they were not to burn out. And that it was the director who always took the decisions!

Susan commented on the maturity of Shale and António and also how articulate they both were. She thanked the dancers profusely saying how sorry we all were that we could not meet them in person.

Written by Trevor Rothwell and edited/approved by António Casalinho, Shale Wagman and Amanda Jennings

© LBC